In third grade I was pulled aside to participate in a survey about books because I was reading at a high-school level and testing off the charts. The lady administering the survey and I sat in the corner of the classroom in tiny desks facing each other while she asked me questions, the first of which was what was my favorite book.

I had no idea how to answer this question because it seemed impossible to answer – far too broad a question because I read everything I could get my hot little hands on including but not limited to Charlotte’s Web, Beverly Cleary and Judy Blume’s entire oeuvre, Flowers in the Attic, The Hobbit, the illustrated book of Bible stories I convinced my mother to buy from the evangelical door-to-door salesman, my dad’s stack of Penthouse magazines that he kept on his nightstand and thought we didn’t know about (or worse and more likely, didn’t care), and whatever else I could find. I was particularly drawn to books by their covers, which is what attracted me to the delightful horrors of V.C. Andrews, which I filed away in my young brain for safekeeping. I wanted to give the right answer, but not knowing what that was, I went with honesty. “Just Me and My Dad by Mercer Mayer,” I said. The book belonged to my baby sister and I read it to her, and to myself, often, along with the rest of the books in that series.

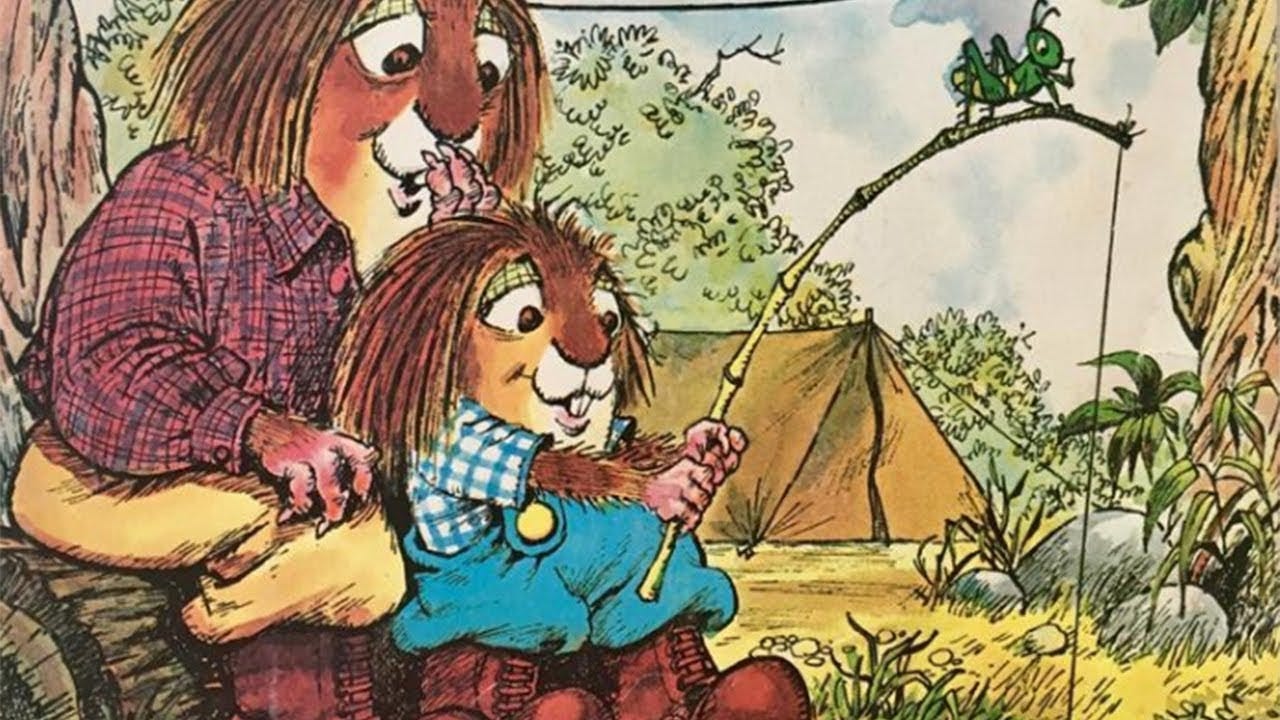

This little porcupine had agency, and the grasshopper that mirrored his emotions was the best.

The survey lady paused with her pen above the paper and asked, “Are you sure?” I could sense her disapproval, and my brain worked to ascertain why. I was pretty sure she wanted me to name a bigger book, something with more pages, and that suspicion was confirmed when she pestered me to list more books I’d read in my lifetime, teasing out a list of titles far more substantial than the book I’d named. Still, I held firm. Nonplussed, she wrote down my answer and proceeded with the survey, recording the reasons for why I’d chosen Just Me and My Dad, a children’s picture book illustrating the home life of a loveable family of porcupines who learn valuable life lessons in a neat and tidy fashion. I followed all of these porcupines’ adventures with a great deal of interest. The reasons I gave her for liking this book were following:

I liked the pictures.

I liked that during their just-me-and-my-dad camping trip the little porcupine screwed everything up, losing their fish dinner to a hungry bear and sinking their fancy canoe, yet his porcupine dad didn’t beat him, he mostly just stood quietly in the background with a look of benevolent acceptance and occasional amusement. “Everyone makes mistakes,” I informed the lady taking the survey.

I liked the relationship between the little boy porcupine and his dad.

I liked that the mom and sister porcupine seemed happy all the time

I liked that the little porcupine wore overalls and was always missing one button so the strap of the overalls was falling off but no one gave him shit about his disheveled appearance.

I liked that the porcupines lived in a cozy hut nestled into a grassy knoll. There was always tea and cake on top of a crocheted doily on the wooden table. I was pretty sure the mom porcupine crocheted the doily and I liked that she’d made something pretty for her family. She seemed nice.

I liked that the porcupine parents made the porcupine children brush their teeth before bed, and no one got slapped into the middle of next week for squirting toothpaste all over the goddamn place.

I liked that the porcupine parents tucked the little porcupine all safe and snug into bed at night.

These were a few of the reasons that I shared with the lady taking the survey about why I liked Mercer Mayer’s Just Me and My Dad. Looking back, it occurs to me that many people who police books would do better to pay attention to the red flags the kids wave after reading them. I liked this book because it showed a kid in a safe and supportive environment free of violence and neglect. Way to miss the subtext, lady.

She wrote down my answers and then the survey was over and I had to go back to class with all the dummies who weren’t smart enough to read books like I did, so they didn’t get to participate in the survey, and even though I knew this was the case, I didn’t feel superior. In fact I felt the opposite, like I’d let this survey lady down. My reasons for liking the book were personal but the book was not considered sophisticated. I felt like I was maybe supposed to be embarrassed for liking this book, and so I obliged. I felt shame.

The message one should feel shame for liking something other people feel is not sophisticated stuck with me and I continued to feel shame for reading and loving Stephen King as a teenager in the 80s, when my uncle who was a literature professor chided me for it. King was not up to snuff, in his estimation. Long before King became a darling of the media elite, he was crapped upon in literary circles unlike his equally prolific contemporary, John Irving, whom I loved in equal measure. In fact one might say I was raised by Stephen King and John Irving, for better or for worse. As a teenager from a dysfunctional family I felt safe in King’s world of misfit outsiders surviving amongst monsters and there was ironic value escaping into the safety therein, though I’d have work to do unlearning ingrained male-gaze-approval. King spilled a lot of ink describing how women’s tits looked in t-shirts. Put that in your pipe and smoke it, Steve-O.

I majored in literature in college, and I felt ashamed for liking what was deemed chick-lit, and referred to my annual novel from Elin Hilderbrand, who graduated from the same elite writing program as Irving, as a guilty pleasure. It wasn’t until Jennifer Weiner and Curtis Sittenfeld made a stink about how disparaging people were towards their work as compared to the Jonathans that I had even considered the matter, but Weiner and Sittenfeld planted a new seed in my mind that began to grow.

I started to examine this phenomenon of who gets to decide what has merit and what doesn’t. I saw it clearly when I worked at The Atlantic and suggested we cover The Real Housewives series, of which I was a superfan, and the assignment was given to a man who had never watched an episode who reduced the entire magnum opus to “gosssssip.”

I was in my mid-40s before I rejected the premise that one had to justify what they liked to anyone else, or that any specific work holds more intrinsic value than another, an idea seeded and grown over a lifetime, the origins of which I’m pretty sure I can trace back to the lady with the book survey in third grade. Someone should write a children’s book about that.

Perhaps it will be me.

I love the Mercer Mayer books as well - they are charming, well illustrated, funny, and true. “Just for You” is my favourite. I have a reel mower and my children have literally tried to mow the lawn for me and been too little. These stories are about 50 years old and still beloved for very good reason.

You decide they have merit and so they do. I happen to agree. Which changes nothing except making me want to engage with your post and share my reasons for loving it as well.

As for “gossssssip”, well! Who was that article for? The people who don’t like or watch the show and therefore don’t want to read an article about it? Or the people who love it and don’t want it dismissed? Hmmm. No readership there buddy. Great decision. 🙄

I’m enjoying everything I’ve read of yours. Thanks for writing and sharing. It’s amazing what writing can be found when it isn’t filtered through the patriarchy. ❤️

Thank you so much. It’s lovely to connect with thoughtful readers.🥰